(With deep thanks to the Minot Daily News for preserving the historical record through its extensive public archives via the Minot Public Library)

On April 4, 1987, a thick black cloud billowed into the skies above Minot, carrying with it the haze of smoke, the stinging acrid stench of chemicals, and the uncertainty of an unfolding disaster. What began as a routine Saturday morning soon transformed into a public emergency, forcing more than 10,000 Minot residents to flee their homes. The source: a fire ignited inside a chemical warehouse on Minot’s southeast edge, sending toxic fumes drifting North over not just the bulk of Minot, but all the way into Canada. Today, the memory of the Westchem fire lives on in the city’s distant memory, but it offers a great view into a disaster that could've ended much worse.

At approximately 11:05 a.m., flames erupted from a Ford F-250 pickup truck parked inside the Westchem Agricultural Chemicals Inc. warehouse on 27th Street SE, where today's Menards is located. The truck, later found to have an "improperly wired aftermarket dome light connected without proper circuit protection", became the unexpected ignition point. The fire spread rapidly through the cement block warehous, and quickly reached barrels of pesticides and herbicides, including parathion and malathion, two toxic insecticides.

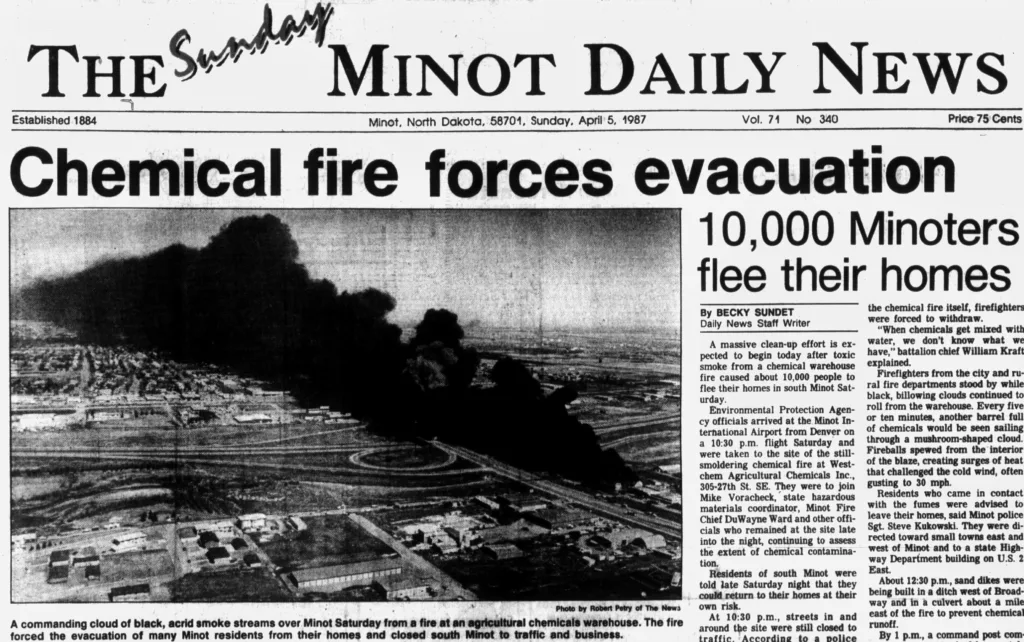

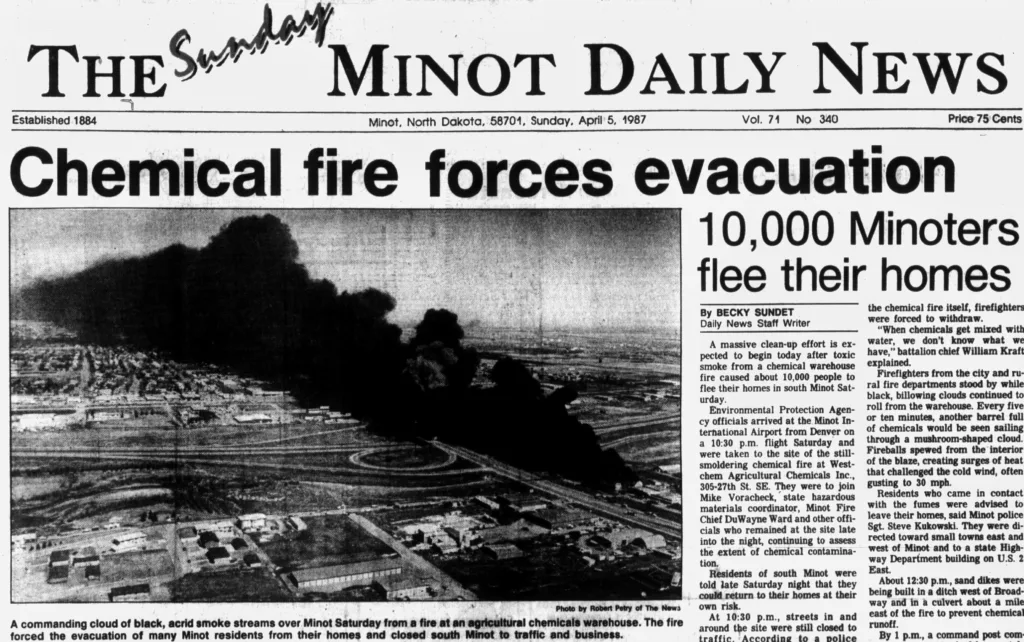

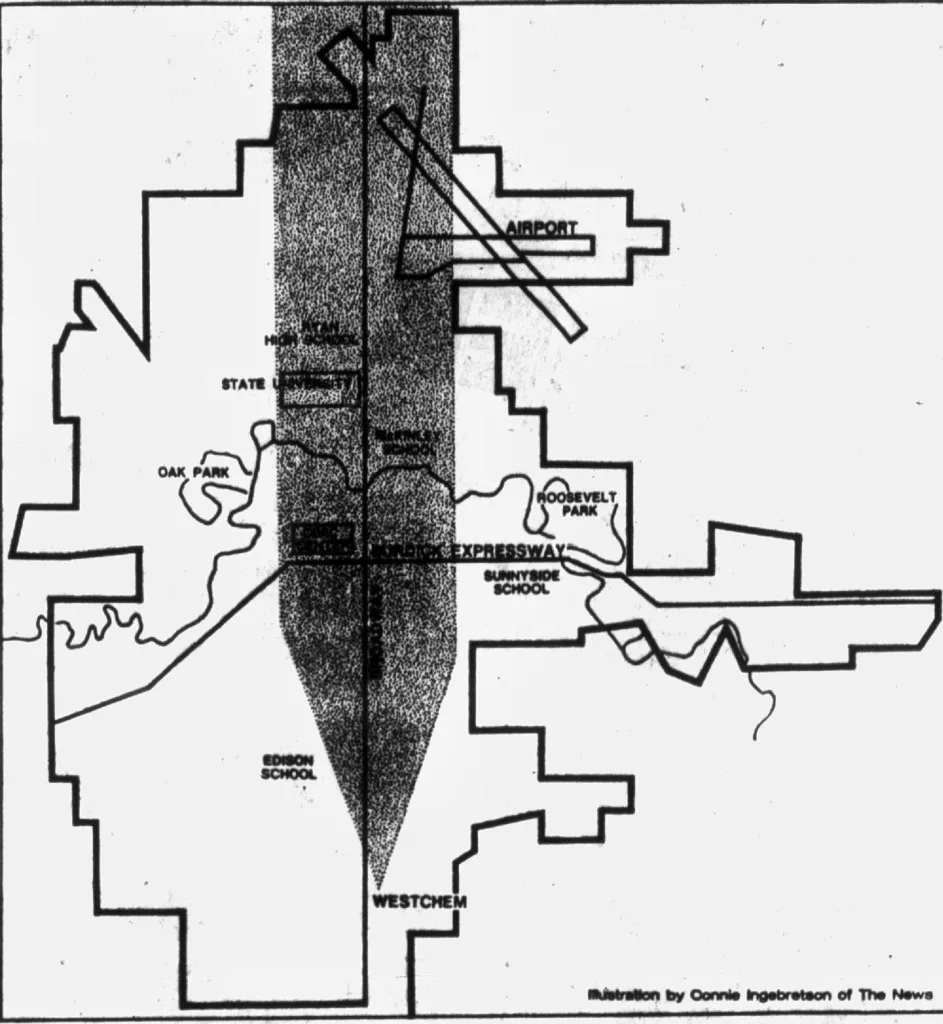

The fire grew at an intense pace, feeding on chemical fuels and actually exploding drums. Flames soared more than 40 feet in the air, sending fireballs mushrooming into the sky that were seen from North Hill. Within minutes, a thick black toxic cloud began to drift northward over the city. Winds, which are predominently out of the NW, were gusting up to 30 miles per hour, and coming out of the South. This carried the cloud straight up Broadway, cutting a swath of fumes up to seven miles north, with some smoke reportedly reaching 50 miles into Canada.

With little time and no formal evacuation orders in place, police, fire, and civil defense officials scrambled to act. Firefighters from Minot and nearby rural departments poured in, along with reinforcements from Minot Air Force Base and the city airport station. But as the first 3,000 gallons of water were used to slow the spread, responders quickly realized that water only worsened the situation, potentially pushing chemicals into storm drains and the water table. By noon, foam was ordered, but responders had to wait for the fire to burn down before applying it at the danger of mixing water with unknown chemicals. The warehouse was reduced to a skeletal shell by 4 p.m., with flames smoldering well into the night.

Over 10,000 residents were told to flee their homes all across Minot with smoke traveling through some of the most densely populated parts of the town. Emergency shelters were established in Surrey, Burlington, and even inside a state highway department garage, with sirens blaring every ten minutes. Police warned residents to shower, bag their clothes, and stay indoors if they’d been exposed. Emergency rooms across Minot overflowed with people suffering from headaches, dizziness, stinging eyes, nausea, and shortness of breath. Firefighters and police officers were among the 40+ treated. Thankfully, despite the seemingly massive fallout, no lives were lost.

By Sunday morning, federal officials from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) arrived from Denver, joining state health officials, North Dakota’s fire marshal, and Governor George Sinner to assess the damage. Soil and water contamination quickly became the central concern. Toxic runoff had already pooled in drainage ditches, with officials plastering the area with specialized sponges to soak up the chemicals. Lab testing later confirmed traces of pesticides like 2,4-D and MCPA, prompting the city to erect sand dike barriers to prevent any further spread.

Officials feared long-term leaching into Minot's underground aquifer system. The State Health Department began what would become a multi-year soil monitoring program, with testing continuing into 1992. Instead of transporting the contaminated soil to a landfill, Westchem’s general manager Harold Schultz opted for an emerging technology: bioremediation. The company Ecova Corp. was hired to introduce microorganisms into the soil. The microbes, fed with water and nutrients, consumed 96% of the hazardous chemicals within three months, becoming one of the first large-scale uses of microbial cleanup in U.S. history, preventing what could have been a decades long contamination.

The disaster,as is common place in America, inevitably led to litigation. In 1986, Westchem had purchased the Ford F-250 pickup from Westlie Motor Company in Minot. The vehicle included a trailer tow wiring harness with a hot wire, protected by a fusible link. But a Westchem employee had spliced an aftermarket dome light into the truck’s wiring, without adding fuse protection, and then proceeded to wrap the new wire around a nylon gas line. When the wire shorted out, it melted through the gas line, igniting the truck and starting the fire.

Westchem sued Ford and Westlie, alleging the truck was defectively designed and that neither manufacturer had warned of such risks. But in 1993, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit ruled that Ford bore no liability. The court found the truck to be safe as it was designed, and that Ford had no duty to anticipate unsafe aftermarket modifications. The claim against Westlie was mostly dismissed as well, though one narrow claim of negligent maintenance was remanded for further proceedings. Ultimately, Westchem was found responsible for its own loss, since Westlies didn't make the aftermarket modification. A legal conclusion that capped a saga of fire, smoke, and fallout spanning over 7 years.

In the wake of the fire, Minot’s City Council passed numerous ordinances to regulate the storage of hazardous materials, no longer allowing them to be stored in mass quantities in town. Businesses were required to submit chemical inventory packets, install lock boxes for emergency responders, and clearly label tanks and containment areas. The fire cost Westchem an estimated $8 million and forced the company to relocate its storage operations outside city limits. The Minot Fire Marshal at the time would later describe it as the first major U.S. chemical fire involving agricultural pesticides, a grim milestone that placed Minot in the national spotlight. Officials across the country would go on to study the city’s response as a case study in emergency preparedness.

Though the flames of April 4, 1987, have long since faded, the Westchem fire continues to cast a long shadow for those thst remember. It remains a cautionary tale about preparedness, responsibility, and the delicate balance between industry and community safety. There were no fatalities, but the fire left behind thousands of disrupted lives, a costly environmental cleanup that helped prove the merit of microbes, and a lasting lesson in how quickly what is seemingly minor negligence could ignite disaster.

And again, a big thanks to the Minot Daily News archives, preserved through the Minot Public Library, so we are able to remember not just the details, but the urgency, confusion, and resilience that defined Minot in the immediate aftermath.