MINOT, ND — Flashback to early 2002: 9/11 was still fresh in Americans’ minds, the New England Patriots had yet to win a Super Bowl, and the L.A. Lakers were in the midst of the Shaq and Kobe dynasty. In North Dakota, Governor John Hoeven was just into his second year, all three seats of our congressional delegation were held by Democrats, and Minot’s mayor was former police chief Carroll Erickson.

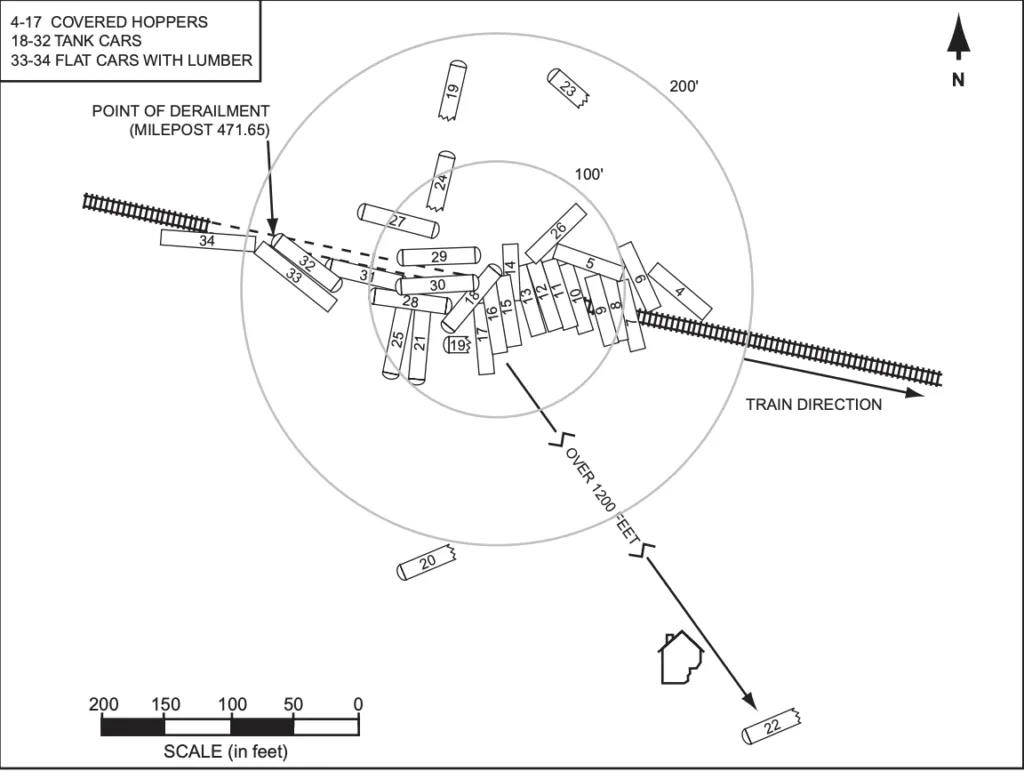

So, on a cold winter night west of Minot, just after 1:30 a.m. on January 18, the screech of metal and a loud and ground shaking series of blasts jolted awake the western edge of Minot. A Canadian Pacific freight train, well over a mile long and hauling more than 12,000 tons of freight, had derailed as it entered a gentle curve near the Tierracita Vallejo neighborhood. Of the 112 cars on the train, 31 fully left the tracks, including 15 tankers that just happened to be filled with pressurized anhydrous ammonia. Five of those tanker cars ruptured catastrophically.

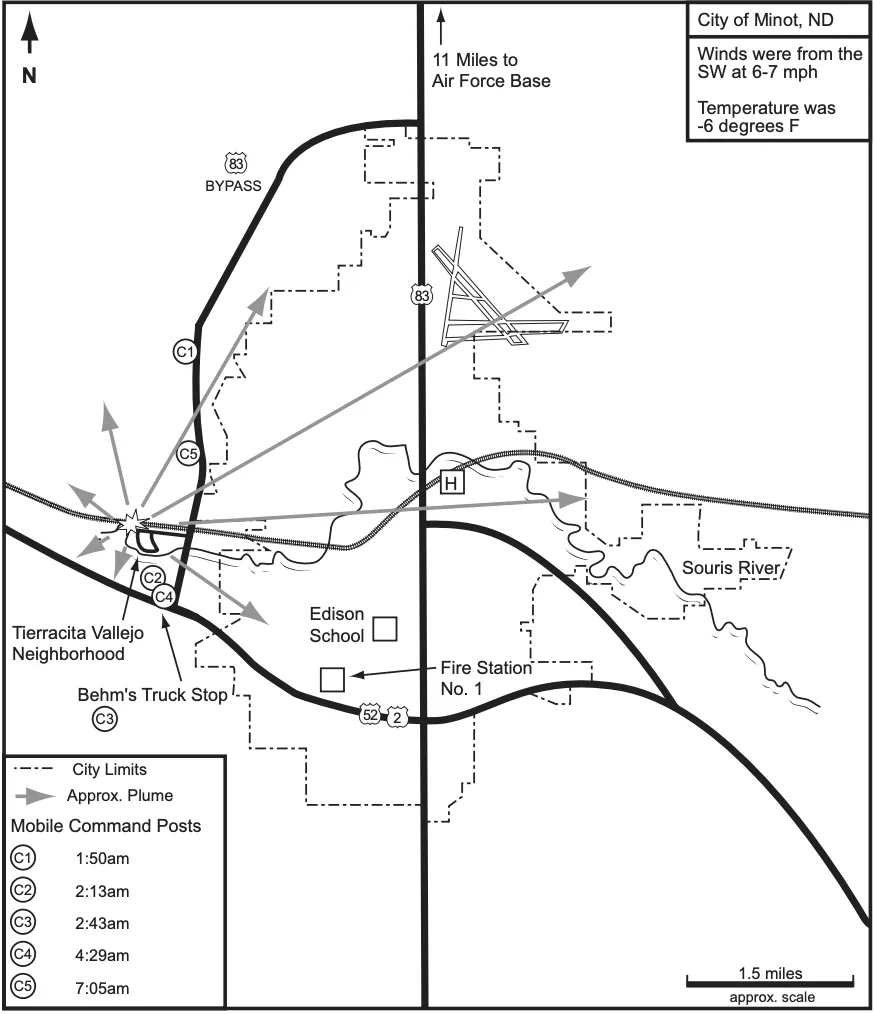

In the wintery subzero darkness, some 147,000 gallons of ammonia gas exploded into the air. It formed a thick fog that clung to the frozen valley floor and drifted with the wind, directly toward sleeping Minot. The cloud stretched hundreds of feet high and rolled eastward, right through the valley into the heart of Minot. Within a matter of minutes, the city now faced a full-blown chemical emergency.

The noxious and pungent gas struck fast and without discrimination; it would almost certainly disorient anyone outside and burn their eyes and throats. John Grabinger, 38, and his wife tried to evacuate their home shortly after the derailment, but their truck crashed into a neighbor’s house in the blinding ammonia cloud. While the neighbors were able to bring his wife inside, John collapsed outside in the yard, exposed to the gas for over three hours before rescue teams could reach him. He tragically didn’t survive. More than 300 others would also report injuries, from chemical burns and respiratory failure to long-term complications like chronic cough, vision problems, and persistent skin irritation.

Minot’s Warning System, Or Lack Thereof

What turned a disaster into a more scrutinized, citywide crisis wasn’t just the chemical spill, it was the vacuum of public information. The systems designed to warn residents in theory failed almost entirely in practice.

Minot’s emergency alert infrastructure relied heavily on radio and television broadcasting, but those systems were effectively paralyzed. The area’s dominant radio provider, Clear Channel Communications, owned six of the city's stations at the time, including the designated emergency broadcast station, yet only one employee was reportedly on duty that night. When dispatchers tried to contact the station to activate the Emergency Alert System, the phone lines were jammed with incoming calls from residents seeking information.

At the time of the derailment, Minot’s designated emergency television broadcaster, KMOT, had no overnight staff on-site, a standard practice for many smaller-market stations in the early 2000s. As a result, even though emergency officials attempted to contact the station to issue live warnings, there was no one on-site to interrupt programming or relay critical information until much later when the station director was contacted at his home. As a result, critical shelter-in-place warnings were delayed or never broadcast at all, leaving residents even more confused on what to do.

The city’s emergency sirens, positioned mostly within the core of Minot, were not heard in the Tierracita Vallejo neighborhood or other outlying areas, exactly where they were needed most. Power outages from the blast in some parts of the city knocked out televisions and radios entirely. And in a time without internet-enabled smartphones, most residents were cut off from real-time updates unless they had a battery operated radio. This led to an influx of calls to Minot’s 911 dispatch, where operators repeatedly advised residents to shelter in place or tune in to the city’s emergency broadcast radio station which, at that point, wasn’t broadcasting any updates.

For those in the path of the gas cloud, there was no clear instruction immediately; no direction on whether to stay put or flee. Some ran into the fog in a desperate attempt to escape only to turn back when the gas burned their throats. Others stayed inside but didn’t know to seal windows or shut down ventilation systems, allowing the gas to seep in. The result was chaos, panic, and unnecessary exposure.

Emergency Response

Despite catastrophic communication breakdowns, Minot’s first responders mobilized immediately, even as the scope of the disaster outpaced what they could initially do. Within minutes of the derailment at 1:37 a.m., the Minot Rural Fire Department scrambled six units toward the scene. Mutual aid was immediately requested from the City of Minot and Burlington Fire Department, initiating the start of what would be one of the largest joint response efforts in the region’s history.

As crews arrived near the Highway 83 bypass and what was then Behm’s Truck Stop (now Pilot Flying J), they were met not by flames, but by a strong stench and rapidly expanding plume of anhydrous ammonia. The gas was spreading rapidly, pooling in the valley, and climbing above treetops. Visibility was poor, breathing was difficult, and any delay risked both civilian and responder lives. Realizing the location was dangerously exposed, then *Burlington Fire Chief Harold Olson made the critical call to pull back and establish a new command post on higher ground, near the city landfill. That decision likely saved dozens of responders from injury or possibly worse.

From that new vantage point, the emergency response took shape. Trinity Hospital activated its Code Green mass casualty protocol, alerting additional staff and prepping triage capabilities. City school buses were repurposed as rescue transports, deployed to retrieve those trapped in the path of the gas cloud. Edison Elementary was converted into a fully operational triage and evacuation hub by 4:00 a.m., with nurses, doctors, and paramedics preparing for worst-case scenarios.

By 4:15 a.m., Trinity reported the chemical fog had reached into downtown Minot. With the situation escalating, the Minot Air Force Base dispatched ambulances, medical staff, and a base physician to assist civilian crews. Even the airport was shut down entirely to prioritize emergency movement and airspace control.

Between 5:30 and 8:20 a.m., rescue teams made a coordinated push into the heart of the vapor zone, wearing full breathing apparatuses to evacuate residents already suffering from disorientation, vomiting, and chemical burns. Several attempts had to be aborted and retried as responders regrouped and re-equipped in the face of worsening conditions. The work was slow, dangerous, and arduous, but ultimately, more than 60 people were pulled from their homes, many likely just in time. As daylight broke and temperatures began to rise, the ammonia cloud started to lift and it was soon clear the worst case scenario was avoided.

The City That Didn’t Hear the Alarm

As the sun rose over Minot, the wind picked up, and the chemical fog lifted relatively quickly. The night exposed more than the vulnerability of lax rail line inspections, it revealed critical fractures in Minot's public warning systems.

Local leaders and ordinances would soon face scrutiny not just from their own citizens, but from the national press and federal investigators. In the months and years ahead, hearings, lawsuits, and legislation would all reach back to that frigidly cold January night when a train derailed, a city nearly choked in the gas, and numerous lives were changed forever.

The fog may have lifted by morning, but the full cause of the derailment, and the institutional failures that allowed it, would not come into focus for months, leaving a multitude of unanswered questions. And the most important one of all: If it happened again, would Minot be up to the task?

[To be continued next week in Part 2: Aftermath and Cleanup]

*edited 5/5/25 at 20:15 for clarification