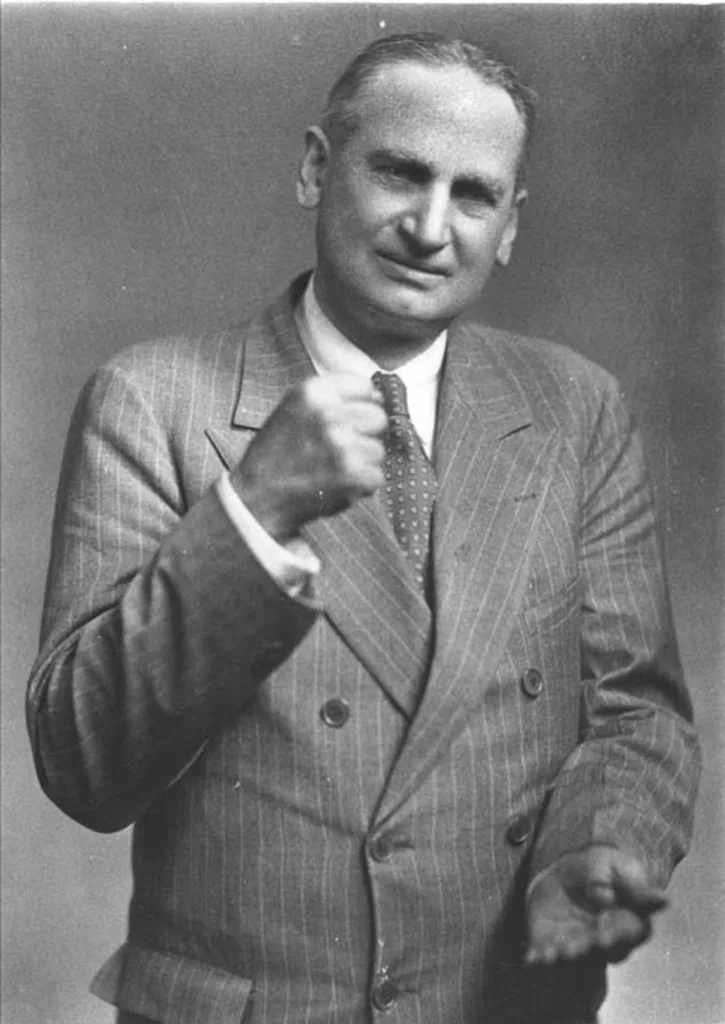

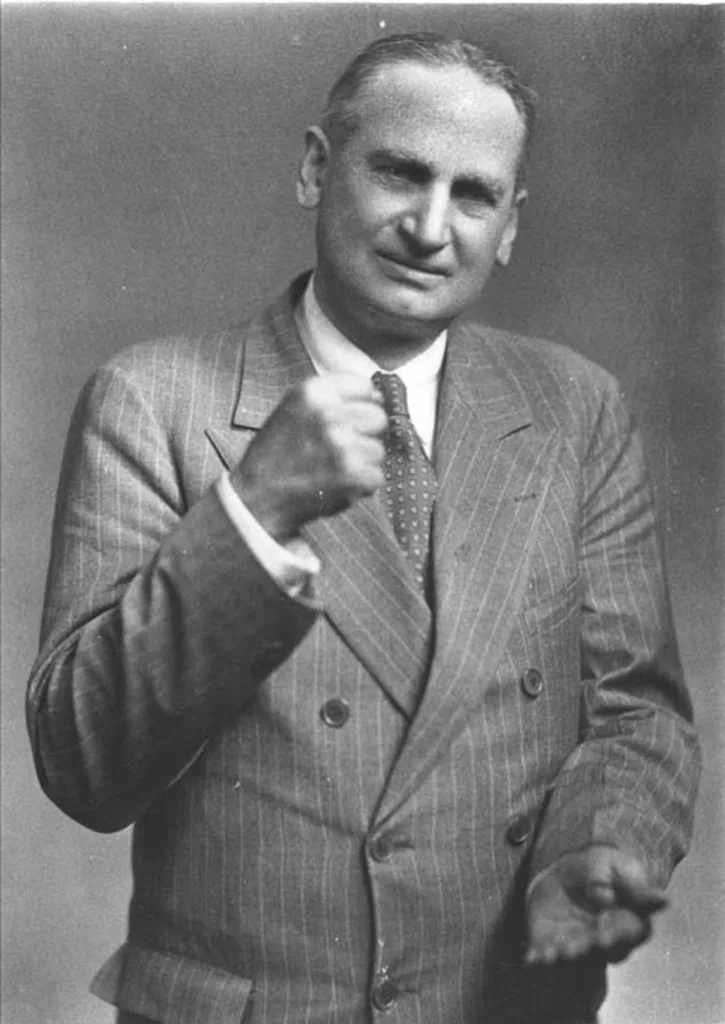

William “Wild Bill” Langer remains one of the most controversial, charismatic, and enduring figures in North Dakota’s political history. A lawyer, reformer, outlaw governor, and longtime U.S. senator, Langer’s life embodied the contradictions of prairie populism: deeply rooted in the struggles of ordinary people, yet unafraid to bend, or break, the rules of the system he claimed to reform.

Born in Casselton, Dakota Territory, in 1886 to German immigrant parents, Langer grew up speaking both English and German and later credited his rural upbringing for shaping his fierce independence. He studied law at the University of North Dakota and then Columbia University, earning his degree in 1911 and returning home with a newly honed legal mind and a taste for politics.

Langer entered politics during the rise of the Nonpartisan League (NPL), an agrarian populist movement that emerged in response to the monopolistic practices of grain companies, banks, and railroads in North Dakota. The NPL’s vision of farmer owned institutions and state-run services resonated with Langer, who embraced their message of economic justice, but also maintained his trademark confrontational style. In 1916, he was elected North Dakota’s attorney general at just 30 years old, quickly earning a reputation as a no-nonsense enforcer. He cracked down on bootleggers, railroads, and frankly, anyone who crossed him, often using the press to publicly shame political opponents.

By the 1920s, Langer had a growing statewide following, but his relationship with the NPL began to deteriorate. He split with its leadership, accusing some of them of being Bolsheviks, further sharpening his anti-establishment Maverick image. Upon mending some rifts, he finally broke through in 1932, elected governor during the darkest days of the Great Depression, running a populist campaign that promised direct aid to struggling farmers and workers.

Langer’s first term as governor was one of the most dramatic in state history. Facing widespread economic collapse at one of the deepest points of The Great Depression, he authorized emergency measures including the issuance of state-issued scrip when banks failed and supported aggressive tax relief for farmers. He also revived an old NPL tactic by requiring state employees and party supporters to contribute part of their salary to a political fund and newspaper, an act that would land him in legal trouble.

In early 1934, Langer was indicted and then convicted of conspiring to defraud the federal government due to those salary kickbacks, which would have been legally fine had it not involved federal workers being paid from relief funds. He was removed from office by the state Supreme Court that summer, but refused to leave. Instead, Langer locked himself inside the governor’s office, declared martial law, and dared authorities to drag him out. He kept the standoff going until his top aides and officers refused to recognize his authority, eventually accepting the courts ruling and leaving without incident.

This unprecedented standoff was just the beginning of a tumultuous 6 months in North Dakota. It saw 4 separate governors serve after Ole H. Olson succeeded Langer, and then that falls winner, Thomas Moodie, was deemed ineligible to serve having not been a resident in the state for 5 years after only serving in the role for a few weeks. This led to Moodie's Lt. Governor Walter Welford to effectively serve out a full term as Governor.

The conviction of Langer was later overturned on appeal citing a biased jury, and Langer then launched one of the most astonishing political comebacks in state history. He was re-elected governor in 1936 as an Independent, portraying himself as a martyr of the establishment and a champion of the people. His second term was less chaotic, and he chose not to run for re-election, instead challenging incumbent Republican Senator for the seat in 1938. Langer, would ultimately be defeated in that bid and would serve out the remainder of his term as Governor before setting his sights on 1940.

In 1940, Langer made the leap to national politics, finally winning election to the U.S. Senate as an Independent, where he would serve until his death in 1959. His tenure in Washington was, in many ways, just as tumultuous as his governorship. He refused to align himself fully with either party, often caucusing with Republicans but voting independently on key issues, furthering his "Maverick" label.

Langer’s Senate record was a mix of progressive populism and eccentric isolationism. He supported farmers, strongly opposed foreign wars, and routinely called out Wall Street and East Coast elites. He was one of the few senators to vote against the United Nations Charter, and in 1951 introduced a bill to make war itself illegal.

But Langer’s erratic behavior and conspiratorial thinking often overshadowed his policy work. He was known to conduct bizarre hearings, push fringe theories on the Senate floor, and continue feuds long past their political relevance. He was also formally investigated by the senate with the body never pursuing formal charges. Despite criticism from the national press and fellow lawmakers, he remained wildly popular in North Dakota. His ability to connect with rural voters, particularly those who felt abandoned by both parties, kept him in office for nearly two decades.

William Langer died in office in 1959, still holding his Senate seat at the age of 73. He was buried in St. Leo’s Cemetery in Casselton, the town where his incredible journey began. Though his career was riddled with controversy and legal battles, Langer left behind a powerful political legacy.

He showed that charisma, populist rhetoric, and grassroots loyalty could sustain a political career even in the face of institutional opposition. His brand of politics was anti-corporate, anti-elite, pro-farmer, and unapologetically personal, would influence generations of North Dakota politicians, frequently hearing "Wild Bill" referred to decades after his passing.

Langer’s legacy remains divisive: to some, he could be seen as a reckless demagogue who abused power; to others, he was a champion of the people who never stopped fighting for the underdog. But few would dispute that “Wild Bill” was one of a kind. In North Dakota’s long history of plainspoken, practical politicians, Wild Bill Langer was the rare figure who redefined the rules, and dared the system to stop him.