I joined The Dakotan with aspirations of making documentaries, and while that remains a goal, I felt the need to share one of the stories I planned to bring forward. Imagine a large-scale military siege unfolding just south of Minot in an unmarked modern day field. An event largely forgotten by history, overshadowed by the Civil War and later Indian wars, yet, in the summer of 1851, such a battle took place. A little-known confrontation occurred between Métis buffalo hunters from the Red River Valley and Yanktonai Sioux warriors under Chief Medicine Bear. It’s called The Battle of Grand Coteau.

The mid-19th century was a period of enormous transformation across North America. Millard Fillmore had just assumed the presidency following Zachary Taylor’s death, westward expansion was accelerating, and the Oregon Trail and California Gold Rush drew thousands of settlers westward. Amid this migration, the buffalo fur trade was thriving, propelling Métis traders into the vast plains in large hunting parties, tracking the massive herds that roamed the Great Plains.

The Métis were descendants of European fur traders, primarily French, and Indigenous peoples; they were a unique cultural group, predominantly Catholic and French-speaking, with deep roots in the Red River Valley near present-day Winnipeg. Each summer, after the spring planting season, Métis hunting caravans would set out in search of buffalo, traveling in massive convoys of carts, families, and provisions.

Opposing them in this battle were the Yanktonai Sioux, a nomadic warrior society that commanded large swaths of land across the northern plains. Their leader, Chief Medicine Bear, would later sign the treaty that established the Fort Peck Reservation in Montana. But in 1851, he commanded a force of up to 2,000 warriors and sought to defend traditional Sioux hunting grounds from what they saw as increasing Métis incursions.

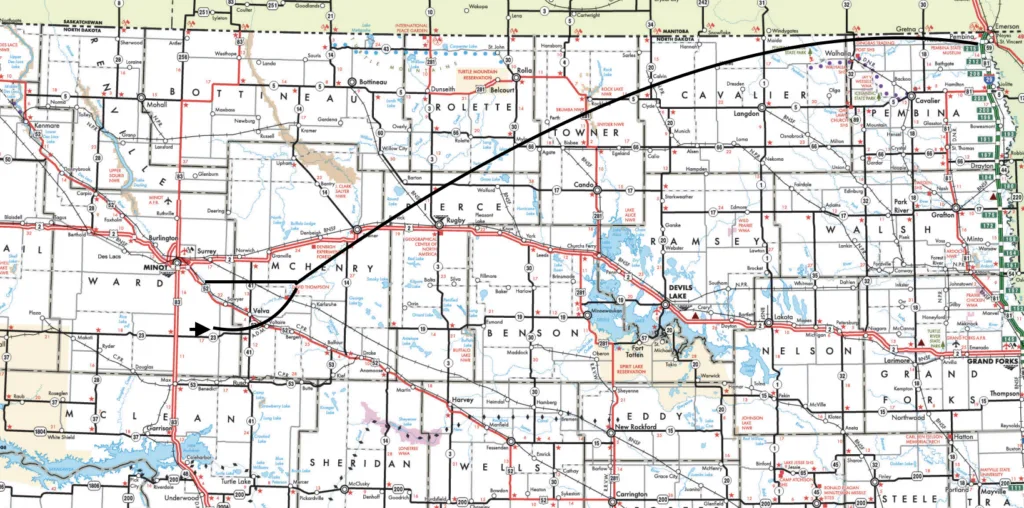

In June 1851, a Métis hunting party departed from the Pembina River, numbering approximately 380 horsemen and 300 carts. Their route took them southwest across what would later be North Dakota. On July 12, a smaller group of about 70-80 hunters, led by Jean-Baptiste Falcon, split off to encircle a large buffalo herd. Falcon, the son of renowned Métis poet Pierre Falcon, was accompanied by Father Richer LaFleche, a Catholic priest whose detailed letter remains the only firsthand account of the battle.

That afternoon, Falcon’s scouts spotted a large encampment on the horizon. Unsure whether they had found friends or foes, Falcon decided to take no chances, ordering the Métis to move to a defensible hilltop position on the Grand Coteau. However, a scouting party sent ahead to gather intelligence made a critical mistake, they ventured too close. Three Métis scouts were captured by the Sioux, confirming the worst fears of the hunters: they were in imminent danger.

Recognizing the threat, the Métis immediately began fortifying their camp overnight. They arranged their carts into a defensive perimeter, a well-known Métis tactic called la corral, using the carts as barricades and reinforcing them with supplies, wooden stakes, and anything available for cover. Trenches were quickly dug beneath the carts to shelter women and children from incoming fire, and small redoubts were constructed just outside the perimeter to provide additional defensive positions for the hunters. Meanwhile, runners were sent in a desperate bid to alert the larger hunting party.

At dawn on July 13, the Sioux war party advanced, confident in their overwhelming numbers. Father LaFleche later recalled the sight: “We are facing a camp of 1,800 lodges… they wanted to enter our camp to raze everything.” Sioux warriors on horseback and on foot surrounded the hilltop, preparing to storm the Métis defenses. But the Métis, despite being vastly outnumbered, held their ground.

(Black line signifies the parties rough track departing Pembina with the split occurring shortly before battle. The approximate battle location is the black arrow-map courtesy NDDOT State Highway Map 2025-2026)

The first Sioux charge was met with disciplined volleys of musket fire. The Métis, many of whom were seasoned hunters, fired with precision, using a methodical rank fire tactic to maintain continuous gunfire. The Sioux, skilled warriors accustomed to mobile combat, found themselves unable to break through the well-prepared defenses. Father LaFleche moved through the ranks, shouting words of encouragement to the defenders as bullets whizzed past.

The siege raged for a full day going from July 13-14. Again and again, Sioux warriors surged forward, only to be repelled by steady musket fire. As the Métis fought to conserve their ammunition, they supplemented their defense with knives and tomahawks, prepared for close combat if necessary. At one point, a Sioux warrior attempted to breach the barricade but was shot down just as he reached the carts.

By midday, the battle’s momentum shifted. The relentless resistance from the Métis began to wear down Sioux morale. According to LaFleche’s account, a Sioux chief allegedly (and I do mean allegedly) shouted in frustration: “We cannot kill the French; they are crushing us. Warriors, let us go.” Just like that, the Sioux forces began to withdraw. Though estimates vary, between 15 and 80 Sioux warriors were killed in the assault, while the Métis suffered no fatalities—except for the tragic execution of one of their captured scouts.

Following their victory, the Métis reunited with the larger hunting party. Some hunters pushed for some kind of counterattack to avenge their fallen comrade, but the group ultimately decided against further bloodshed. Instead, they continued their hunt, though the battle had disrupted their efforts, and they returned home with fewer hides than expected.

Before departing, they left a message tied to a pole, warning the Sioux to respect their right to hunt and condemning their aggression. The note, written in English so an American interpreter could read it, concluded with a sharp rebuke: “It was against the inclination of our heart, and even with great reluctance, that we were forced to fight with you. It is your doing. We only had 80 armed men in our camp; you had possibly no less than 2,000 warriors. And yet, see now the results of two attacks.”

Father LaFleche would go on to become a bishop in Quebec, while Jean-Baptiste Falcon lived out his years in Manitoba. Chief Medicine Bear survived well into the early 20th century, continuing to record his people's history through a traditional Winter Count.

Today, the Battle of Grand Coteau remains a footnote in history, its battlefield now private farmland in southern Ward County. The only serious research into the site was conducted by historian Lawrence Barkwell, who led expeditions in 1987 and 2011 to confirm its location. His work remains the most comprehensive study of this remarkable event.

Ultimately, the Battle of Grand Coteau serves as an early warning of the escalating conflicts that would come to define the American frontier. It remains an extraordinary yet brief and overlooked chapter in North Dakota’s history. An event that highlights the resilience of the Métis in their pursuit of prosperity and the determined resistance of the Sioux as they fought to defend their way of life against the forces of change.